Homer Simpson, 2nd Level Thinking & Peanuts

April 7, 2022

Read enough Wall Street analysts reports you begin to get a sense of some analysts’ sense and sensibilities, their feel for the world and how they sort through the tornado of swirling information. If we’re being honest, most are hacks. The Pareto principal definitely applies in this realm, as 80% are middling to below average and 20% are worth reading. Sometimes it comes down to age/experience, other times it comes down to how the banks use their research shops (as a sales & marketing tool) or as a thought leader/idea generator. We suppose they’re all sales & marketing tools to some extent, but still, sometimes we do gleam a few decent insights. Occasionally though, a few will provide some insights that are piercing, and when you read a few analyst notes together, you can begin to see a narrative thread emerge.

We have to be careful because the thread we’re pulling on can simply be a byproduct of the Wall Street echo chamber. Still with that caveat in mind let’s take a look at something we’ve been thinking about.

We’ll start with this phrase by Howard Marks that kicked off our train of thought.

First-level thinking says, “It’s a good company; let’s buy the stock.” Second-level thinking says, “It’s a good company, but everyone thinks it’s a great company, and it’s not. So the stock’s overrated and overpriced; let’s sell.”

First-level thinking says, “The outlook calls for low growth and rising inflation. Let’s dump our stock.” Second-level thinking says, “The outlook stinks, but everyone else is selling in panic. Buy!”

First-level thinking says, “I think the company’s earnings will fall; sell.” Second-level thinking says, “I think the company’s earnings will fall less than people expect, and the pleasant surprise will lift the stock; buy.”

First-level thinking is simplistic and superficial, and just about everyone can do it (a bad sign for anything involving an attempt at superiority). All the first-level thinker needs is an opinion about the future, as in “the outlook for a company is favorable, meaning the stock will go up.”

Second-level thinking is deep, complex, and convoluted.

Welcome to Zoltan’s Brain

Zoltan, is Zoltan Pozsar, a native of Hungary, for the past 7 years, he’s been with Credit Suisse (“CS”), as their Global Head of Short-Term Interest Rate Strategy. Prior to CS, he was a senior adviser to the US Dept. of Treasury and before that the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. He’s steeped in the Fed and the intricacies of central banking. Unsurprisingly he writes about macroeconomics, central bank liquidity, and monetary policy. Lately, he’s been writing about money, commodities and Bretton Woods III, which coincidentally is the title of his missive dated March 31, 2022. Essentially this is his view of the current issue:

To paraphrase, since commodities (i.e., “real stuff”) will become the dominant thing, in a world short of commodities it automatically becomes the most “valuable thing.” In turn, he who possesses it also plays an outsize role in determining which currency you can use to trade for it.

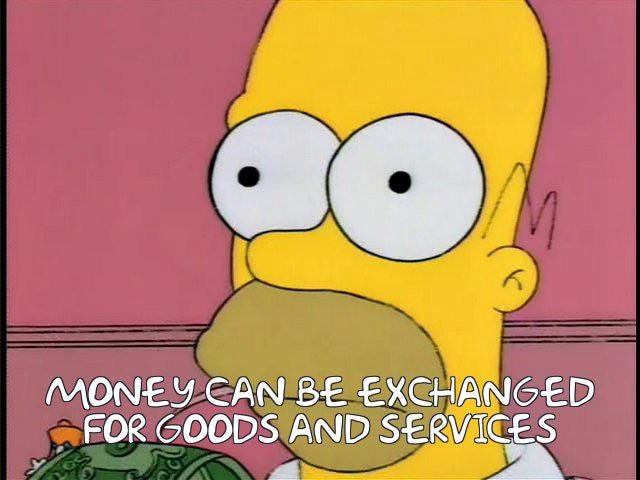

As this Simpsons episode explains:

Brilliant . . . but what money? Who’s money? US Dollars? Euros? RMB? Roubles? Well it depends because in Zoltan’s brain . . . that’ll be determined by whoever controls the commodities, and since those are largely in countries not called the United States, expect our currency to weaken.

He’s not calling for the dollar’s immediate demise, but he is saying that it will be pressured as we move into a commodity constrained environment. Go back to the last sentence of the first caption up top and you’ll see why . . .

You can print money, but you can’t print commodities.

It’s essentially what he’s calling Bretton Woods III. If you recall Bretton Woods II was deflationary because of globalization, open trade, just-in-time supply chains, etc. In contrast, Bretton Woods III, which we will embark on, will be inflationary as de-globalization, autarky, just-in-case hoarding of commodities and duplication of supply-chains occur. All of these things in Bretton Woods III simply costs more. More money, more capital, more manpower and more time. Moreover, as nations become protectionist, hoarding/coveting the scarce resources they possess, these “real” things (i.e., commodities) become increasingly more expensive and prized. The value of “real things” outpacing money and that becomes the dominant thing dominating world trade. In Homer parlance, peanuts = money.

Explain How?!

If peanuts become money, then instead of the usual factors used to value money and measure liquidity (i.e., central banks balance sheets, fed policy, financial stability), we have to look at different metrics that impact the value/trade of peanuts . . . err money:

Trade - who owns what commodities, who sells what to whom, and in what currency;

Shipping - the time it takes to ship peanuts, as time is money; and

Protection - who’s protecting the peanuts against the squirrels.

Put those three things together and you get a sense that if a country owns a lot of peanuts (i.e., commodities), the value (and in turn strength of the currencies they trade with/in) will become paramount, and since peanut/money strength are intertwined, we have to begin to look at the liquidity, security, stability, and volatility of the peanut trade. That’s the cost of a world dominated by a shortage of real things, and we have to reframe what we use to gauge global liquidity. In this new world, call it Bretton Woods III, or whatever, the factors we use will be fundamentally different. But wait, why is liquidity important?

Druck?

“Earnings don't move the overall market; it's the Federal Reserve Board... focus on the central banks, and focus on the movement of liquidity... most people in the market are looking for earnings and conventional measures. It's liquidity that moves markets.” - Stanley Druckenmiller

So you see? Zoltan is saying . . . as real stuff gets more expensive, we really need to reevaluate how we view the world. Liquidity is now based on the movement of peanuts . . . and that won’t cost peanuts.

The Future is Uncertain

Although we were already headed there, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has accelerated and exacerbated the issue. We now find ourselves in a more geopolitically unstable world, one that will have clear knock-on effects on the price of our peanuts. In fact, global instability, commodity price instability and financial instability will become inextricably intertwined in the future.

In the short-run, a more dangerous world begets more price and financial instability, one where the central banks will be hard pressed to solve. Longer-term as commodities become even scarcer, they’ll rise further in value, shifting the balance of power to those who produce it and those who control it. Those who do, dictate who’s money can be exchanged for peanuts, further destabilizing geopolitical balances, which again feeds into the loop.

Whew . . . heady stuff.

But wait there’s more . . .

The second issue he’s been pondering is the lack of financing for the commodity trade. As commodity houses were caught wrong-footed with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the spike in volatility led to margin calls and the retreat of capital/liquidity in the space. Commodity houses began raising capital far and wide, even going as far as asking central banks to backstop them.

That request was quickly bebuffed:

Said another way, liquidity is quickly disappearing from the commodity trading spaces, and with thinner buffers and fewer counterparties, price discovery falls and price volatility increases. In turn, higher volatility exposes more “dollars at risk,” which forces banks to impose even higher margin requirements on traders, further shrinking liquidity. So it’s a vicious cycle, and one of the main reasons why open interest in oil has fallen even as oil prices have soared.

Remember also because of the Russia/Ukraine conflict, peanuts are now being rerouted around the world. The increase in sailing times requires more ships, longer voyages, higher costs. Time is money and it also increases your exposure to the price volatility and risk of loss (storms/pirates/sanctions, etc), so the rerouting will have higher short-term costs. It’s not unlike a rise in short-term interest rates in the “old days” when money was the dominant form of currency and not peanuts.

So higher margin requirements stemming from volatility/geopolitical uncertainty coupled with the higher “friction” costs of longer sailing times = much less liquidity in this world of valuable peanuts.

We know . . . this is tough, but bear with us.

Here’s a last piece of the narrative thread. We’ll throw in an analyst report from Goldman Sachs because it pairs well with what CS is saying. They’re seeing the same challenges on the bank side because of this shift.

Banks? They just weren’t built to handle peanuts.

Concurring with Zoltan, they see the same tensions.

Nonetheless, this is where we’re all headed . . . because again.

You can print money, but you can’t print commodities.

Ultimately, where do we come out after all of the mental gymnastics? If we’re truly beginning a period of time where we’re globally short of commodities (which we believe we are), then we’ll have to reframe how we think about the expansion and contraction of liquidity. The factors and inputs are different, and what we historically look to for guidance will shift. Central banks still matter, but they will have less say in how this all goes because as we paraphrased earlier . . .

You can print money, but you can’t print commodities.

If this new world is forcing the cost of (and the cost to trade) peanuts higher, then prepare yourself for that. Said another way . . . hoard as many peanuts as you can.

Explain How?!

Buy peanuts.

Please hit the “like” button below if you enjoyed reading the article, thank you.

It's not easy to buy commodity (Peanuts in your article) directly for retail investors. I think for retail investors, buying the first-hand commodity producing company stocks (from the Earth) is the most safe and easy way to benefit from the global shortage situation. Public traded companies are very well audited and low-cost to hold on long-term, compared to other futures or options.

Double excellent