Inflation? Buckle-up . . .

August 25, 2020

There’s one way out. It’s the only way out. Once we intentionally sacrificed the global economy in the name of public health, we set ourselves on that path. Debt to GDP ratios are now at levels previously seen only during times of war, and the debts are here to stay as we’ve been filling income holes in the past year. Once buried, once spent, that money can’t be unearthed. So the debt must be dealt with, serviced, refinanced, or repaid, otherwise the economic therapy administered during the COVID crisis becomes our own undoing. A situation where the treatment could be worse than the disease; where the chemo becomes the real killer.

We previously discussed the magnitude of the debt in our prior newsletter (“Global Debt & the Pandemic”), and invite readers to revisit that foundational issue. Now let’s explore the knock-on effects. The “what happens next?” Once we defrost the economy, how do we tackle the debt issue that we discussed in our last issue? Well let’s look at our options.

Default,

Adopt Austerity,

Grow, and/or

Inflate

Growing Pains

The first two options addresses the debt side of the equation, while the remaining two GDP. Since defaulting isn’t possible with a fiat currency (i.e., the US can always print more) this isn’t a realistic scenario, nor is fiscal prudence at this stage. Our Keynesian policy makers will contend that it’s likely more harmful if the government suddenly reduces spending. As it’s the deepest pocket right now replacing income/mitigating unemployment, reducing spend will immediately constrict the economy, so it’s better to run deficits as the economy recovers.

Since defaulting or reining in our fiscal spending is unlikely, we’ll look to juice the denominator (i.e., GDP). Growing your way out of the high debt/GDP conundrum is ideal because you’re creating wealth (i.e., new income streams) to service the higher debt levels. For developed countries like the US, demographics, natural resource constraints, and the evolutionary vs. revolutionary nature of technological advancement presents headwinds to growth. Thus, it’s unlikely that we can grow our way out of this debt conundrum, or to the extent necessary to lower our newly created burden. As US debt to GDP ratios have vaulted 20-30% higher in such a short-time, it’s nearly impossible to increase GDP at a much faster pace to match. Having said that, we’ll certainly try.

In our last newsletter, we posited that Congress will attempt to morph COVID rescue packages into COVID stimulus packages going forward. Infrastructure repairs/improvements and green energy investments (for Democrats) will be the focus of any administration that captures the White House. The size of such packages though will depend on who wins the Senate. If the same party controls both Congress and the White House, expect the legislative roadblocks to fall and the size of these stimulus packages to rise. The themes for such packages will be wide ranging, but they’ll all attempt to do the same thing, energize the economy and create jobs. Prudently invested, the stimulus can catalyze growth in new industries, but frankly Congress hasn’t had a great track record in such matters.

Inflating Expectations

What about this inflation you speak of? Ah now that’s interesting. If it’s too hard to grow our way out of this debt quandary, perhaps we can inflate our way out of it. As you know, inflation is a decline in purchasing power, and it’s driven by a rise in the prices of goods/services when demand outstrips supplies. Now what if demand doesn’t rise? Perhaps we can debase the currency to accomplish the same thing . . . raise prices. Since GDP is the monetary value of all finished goods and services, raising prices will in turn raise GDP, and if the growth in debt stays low, then mathematically the debt/GDP ratio falls. Sure it only increases “nominal” GDP and not “real” GDP as the latter is net of inflation, but who cares, #amiright?

How do we do this? We’ll extend the playbook for what we’ve been doing to counteract the effects of the COVID pandemic. As part of the policy responses to the pandemic, we’ve taken extraordinary measures. To avoid an economic depression, the federal government has engaged in massive fiscal deficit spending; spending that is financed on the monetary side by the Fed’s unprecedented money creation. The central bank has further adopted a zero interest rate policy (“ZIRP”), engaged in quantitative easing and lowered commercial bank reserve ratios to sustain this scenario. Will all of this lead to inflation? Let’s walk through the arguments.

The Case Against Inflation

Regardless of this monetary deluge, some have argued that we’ll actually see deflation as demand stays muted and the money fails to circulate. This is the 2008/2009 Great Financial Crisis (“GFC”) all over again. Those in the deflation camp contend that despite the money creation, the velocity of money has been low. Flooding farmlands doesn’t make crops grow faster. It’s a two-sided problem. Banks are still liable for the credit risk on loans, and in an uncertain economic environment, they’re naturally hesitant to extend credit, which stymies money flow. Moreover, borrowers don’t actually want additional debt right now, and if they did, they won’t invest the proceeds into producing more goods or providing more services. Many of the loans taken out today are to shore up liquidity issues or refinance debt to buttress balance sheets, hardly productive endeavors. Consequently, the money never really circulates into the “real economy”. Lastly, high unemployment and a sluggish economy will mute demand going forward and without demand, there can be no inflationary price pressures.

The Case for Inflation

The inflation camp argues no-no, the COVID Crisis is fundamentally different than the GFC in effects, and hence necessitated a different policy response. It’s different because the COVID Crisis reduced income/liquidity, whereas the GFC was a credit event. In the GFC, governments were concerned with solvency risk as credit markets froze when bank balances sheets became impaired. In the US, this meant authorities directed the lion-share of aid towards saving banking institutions and lowering credit risk. Instead of increasing lending, commercial banks hoarded the money (for regulatory and risk management reasons) to survive.

Favoring big banks and companies while emphasizing fiscal austerity eventually led to a populist backlash in the US. We can draw a line between the policy responses enacted during the GFC and the Tea Party movement, Occupy Wall Street, and Trump/Sanders/Warren campaigns that followed. Consequently as Congress prepared the initial COVID aid packages (i.e., CARES Act), they specifically called for the direct infusion of money into the pockets of individuals and companies. Eager to avoid the criticisms of the GFC and replace income lost due to the draconian public health measures, the federal government rained down money in the form of stimulus payments, PPP, unemployment benefits, grants and forgivable loans, which effectively bypassed commercial banks.

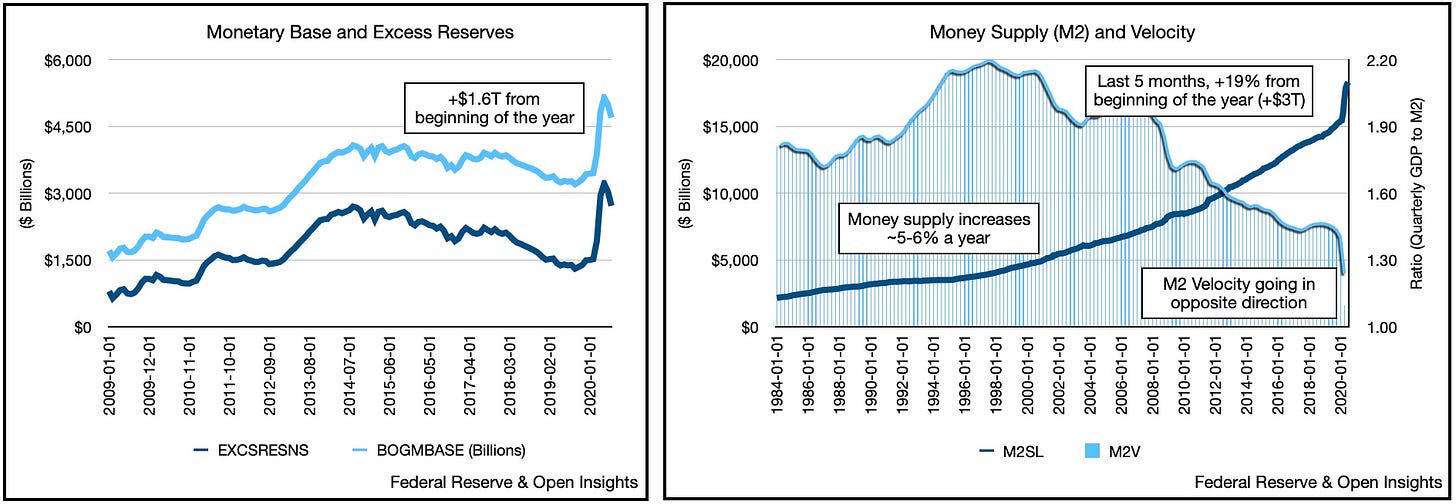

Our current COVID response effectively subserviates the central bank. Engaging in massive fiscal deficit spending means co-opting the Fed to print and fund whatever Congress and the White House decides. What’s better than an accommodative central bank? One that is accommodating and simply funds your fiscal spend. Send money here, guarantee that, fund this, buy that. It’s hard to overstate how much more money has been created and directly injected into the system. Here’s the growth in monetary base and the M2 money supply.

Initially, the money was saved (as a 10% unemployment rate still meant 90% employment), but as lockdowns and restrictions lift and the economy recovers, the velocity of money supply will turn higher as spending increases and the money circulates in the real economy.

In addition, banks are much healthier today, so lending/borrowing will accelerate as incomes recover, particularly amidst the backdrop of the various credit guarantees (which the government can “freely” hand out as these are contingent liabilities) and the Fed’s support of the debt market (buying investment grade/non-investment grade debt to quash risk premiums and ZIRP).

Deflating Deflationary Tailwinds

The inflationary camp also argues that the deflationary forces of the past decade are fading. First, the Fed is shifting to a stance of welcoming/spurring higher inflation. Recent comments from members of the Fed clearly indicate that it will not only tolerate, but favor higher inflation, aiming to overshoot its 2% inflation target to compensate for years of low inflation. Second, what staved off inflation after the GFC were deflationary tailwinds that are subsiding: globalization and the rise of technology. The trend towards globalization is now plateauing and may reverse as trade wars increase (e.g., US/China, increasing protectionism, rise of populism/nationalism, political interference, etc.). The COVID Crisis has also forced companies to reevaluate supply chains and consider resiliency alongside efficiency, which means more on-shoring and higher costs.

As for the rise of tech, it will certainly continue to grow, but their sheer dominance increasingly exposes them to greater regulatory scrutiny. Anti-trust and labor issues are rising, which means added costs. Cutting out the “middleman” will continue, but can wholesale consolidation occur? Will wages stay low as Amazon workers, Lyft and Uber drivers, etc. fight for more compensation? Many tech platforms have succeeded largely via wage suppression, and it’s not hard to imagine that the current practice of classifying de facto employees as independent contractors can survive for long.

So What Is It?

Combine currency debasement (devaluation via money printing and ZIRP), pro-inflationary fiscal and monetary policies (incoming stimulus packages and shift in Fed stance), and fading deflationary tailwinds, we believe we’re headed for inflation. Now certainly this isn’t your cyclical demand driven inflation, which is why this will be a challenging issue for investors and the central bank to navigate. If inflation overheats, will the Fed reverse ZIRP and increase interest rates especially after it adopts a new policy on favoring higher inflation? If so, won’t that directly end the needed inflation because again . . . that debt/GDP ratio? Furthermore, what can they do when politicians have already sipped from the “unlimited” money well, and will want more under the guise of recovery? As we noted previously, deficit spending will add even more money as we transition post-election from rescue packages to stimulus packages. It needn’t even be money that Congress rains from down on high; Congress can provide credit guarantees to expand and lower the cost of capital for green energy/infrastructure companies, and these again will be contingent liabilities as opposed to fiscal spending. The toolkit for money creation has indeed greatly expanded, which means the desire to use it has as well.

About Demand

We’re also not entirely certain that we haven’t created a demand driven inflationary environment. As the pandemic subsides, demand for goods and services will climb, but inventories and supplies will be initially constrained as manufacturing has been muted for most of 2020. Unemployment is also higher, which means workers will need to be reemployed and redeployed, so at least temporarily, there will be a lag between rising demand and limited supplies. This should be temporary though because the companies and factories are still around, and although many will exit the crisis with higher debt levels, wholesale bankruptcies have not occurred. So eventually supply/demand will rebalance as production catches-up (e.g., food/meat processing).

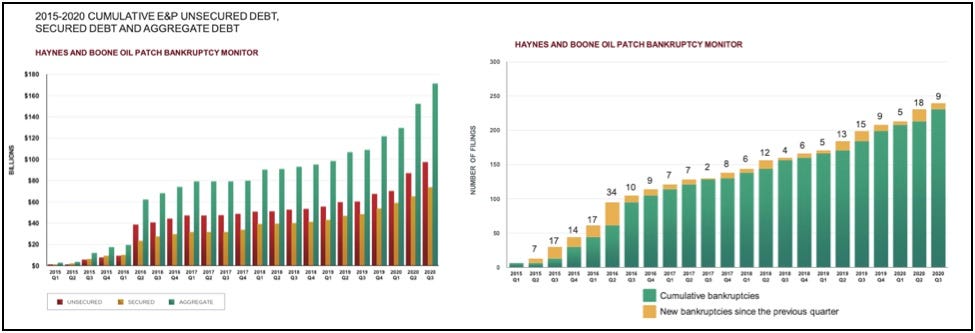

In contrast, other industries like energy have seen the complete opposite. Unlike the airline sector, aviation, or tourism, the US specifically tailored its rescue packages to avoid “bailing out” the energy sector for fear of backlash from environmentalists. Thus, without credit guarantees, grants and direct loans, energy companies have been allowed to fail, taking supply capacity with it. We’ve touched briefly on oil in our third issue, which readers can revisit here.

According to Haynes & Boone’s Oil Patch Bankruptcy Monitor report (July 31, 2020), the number of oil related bankruptcies are rising, and the quantum of debt defaulting has already exceeded the prior 2016 peak.

For surviving companies, their access to capital has also been sharply reduced, so as demand recovers, the supplies simply won’t be there, and if we want them to be, the price to produce the incremental barrels will be much higher than what it is today. Translation: there is no excess capacity = inflation when demand returns. Much of this won’t be reflected in core inflation (i.e., PCE), but energy prices touches almost everything in the economy, so it will indirectly affect everything.

In the end, this is what we’re facing.

This mountain of increased debt, from which we’ve few options other than attempt to inflate our way out of. Watch closely as we do whatever it takes to push (debase our currency) and pull (stimulate growth) our GDP upwards. Both plans point to increasing our monetary base and money supply, increasing loan guarantees and suppressing nominal interest rates for awhile. While the US Dollar’s role as the reserve currency of the world will prevent it from collapsing, it likely won’t prevent it from weakening as the scale of our efforts dwarfs other countries. For a country that perennially runs a current account deficit (as we import more than we export), we’re expecting prices to rise. So for us? The signs point to inflation.

In the coming letters we’ll begin to address what that means for various assets and asset classes, but as promised we wanted to articulate the arguments for both inflation/deflation camps and provide our own views.

Join the Distribution List

So that concludes this letter. We’ll endeavor to send these out weekly, so if you would like to be added to our distribution list click on the subscribe button above. This is our start and it’s our invitation to you to join us and share your thoughts. Welcome to Open Insights and let the conversation begin.