Our Q3 2022 Letter & Look Ahead

October 19, 2022

The tide, the water, the liquidity, call it what you will, but it’s all receding. Backpedaling as central bankers worldwide tighten financial conditions to combat the rising inflation. Warren Buffett once salaciously said . . . .

“Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

Behold, we’re all in a nudist colony. Never have truer words been spoken, as the excess liquidity led to excess, and capital markets morphed into casinos. Things that should’ve never been funded were and private enterprises that should’ve stayed private didn’t. Endeavors best left to hobbyists were financed, marketed, and then foisted onto the ravenous public. Despite their Reddit bravado, retail investors never stood a chance. If there was a SPAC or IPO to be had, out came the spackle to hide any blemishes, and out came the presentations to sell it. Like house flippers, the changes were all superficial.

Our excess capital flowed to a myriad of unprofitable and unproductive ventures in the past few years. We shook our heads because we’ve seen this before. We were there in 2000 when the internet bubble bursted and bought the T-shirt in 2008 when the housing market collapsed. We were carried out with the waves in the former, but with experience and a dash of luck, did well in the latter. Nonetheless, when the water drained, tide pools of wasted and misallocated capital were the hallmarks for both periods.

This time is no different. The companies, technologies, and offerings may have changed, but the froth and overconfidence are the same because human nature never changes, only people’s experiences do. You just wouldn’t understand, they said. You’re too old to get it. No . . . we do. Unlike those younger, we’ve just seen the aftermath once innocence is lost. As the water retreats, the sand castles crafted by charlatans crumble and investors lauded as visionaries are exposed as illusionists; their outsized returns merely byproducts of favorable tides and timing.

So as central bankers withdraw liquidity, someone needs to step-in to refinance or otherwise replenish the capital. Given the unprecedented deluge of global liquidity, even a small tightening of financial conditions will have an outsized impact on asset prices if the handoff isn’t smooth. Yet the prices and interest rates demanded by the public markets to sustain our heightened expectations will be much higher than the evergreen printers churned by our central bankers.

Ponder that for a moment. We’re transitioning from a world where interest rates were near or at zero for more than a decade to one hovering near 5% in less than a year. There’s a whole generation of investors who don’t understand the value of money because money/financing was free. Now we expect them to all to adjust nimbly? Impossible. This will hurt, things will break, moral hazard will return to heighten morale hazard as sentiment falters. It will be a painful, but necessary lesson, that is until central bankers shift from tightening to firefighting. They won’t want to bail everyone out, but choice is a luxury when system failures cascade.

So tighten those draw strings and get a whole lot more sunscreen. The ocean wants its water back . . . it’s naked time.

Heading into Q4

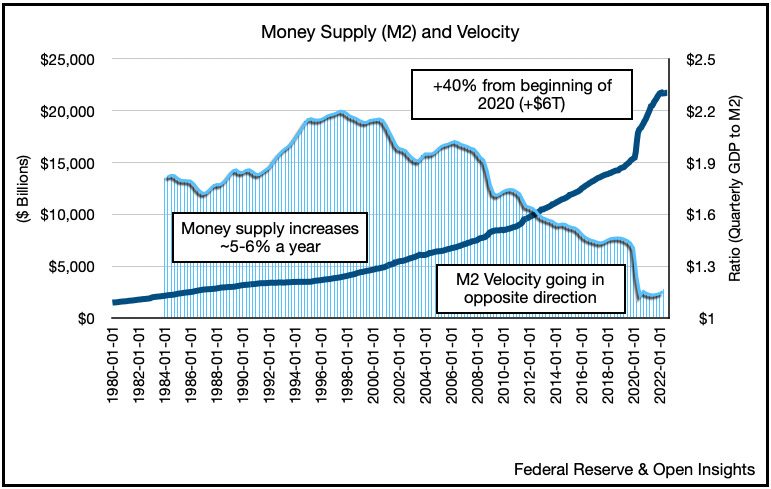

As we enter Q4 in a tumultuous 2022, we’re seeing firsthand what happens to global assets now forced to detox after spending over a decade binging on low interest rates and excess liquidity. Easy monetary policies that started as prescriptive painkillers after the Great Financial Crisis (“GFC”) in ’07/08 morphed into an addiction as falling asset prices became intolerable to a generation of investors. Aided and abetted by politicians and central bankers too willing to accommodate the addiction, we took it to new heights during the COVID pandemic. That black swan gave us the perfect excuse to let it all out.

Remember, earlier this year we were seriously debating the viability of Modern Monetary Theory, an unlimited printing of money to implement universal healthcare, fund universal basic income, forgive all student loans, and make permanent the Child Tax Credit. The step-change in inflation, however, foiled all of it. The reality of life getting more expensive made us reconsider what was a want vs. what was a need. The failure of the Build Back Better bill marked the end of such fiscal folly, but the damage had already been done. We’d already released trillions into the system, and runneth the bathtub over.

So we spent it, we gambled it, and like Scrooge McDuck, swam in it. Everything got expensive. The Consumer Price Index rose a shocking 9.1% YOY in June, and prompted the Fed to swing its hammer.

Throughout the third quarter, the Fed marched on its warpath, willingly trading higher unemployment/job losses for lower inflation. Demand has to be suppressed, otherwise crushing inflation could lead to instability as it entrenches itself into the economy. Behaviorally if we anticipate prices will rise, we’ll pull forward demand by buying things in advance. Hoarding leads to more inflationary pressures, and the vicious cycle perpetuates. So temper demand we must.

“Get out of the water!” screamed central bankers turned lifeguards as they quantitatively tighten and end government bond buying.

“Get ashore!” they yelled as rates were raised aggressively and relentlessly.

When liquidity tightens, the first to go are prices of the riskiest asset (e.g., venture capital, private equity, real estate properties). Those markets go “no bid” as buyers and sellers hold off and circle one another because price expectations are too far apart. Although many investors are refusing to “mark-to-market” the falling asset prices on their investment portfolios, that’s an accounting issue. Reality is different. Many of the unicorns are headed for the glue factory, but no need to get sophisticated, just look out the window and take a peek at your local real estate market. How sustainable are former housing prices when mortgage rates have climbed from 2% to >7% in 10 months?

In Q3, the impact of higher rates began rippling through every asset class. The credit markets first, then the stock market. By quarter-end, there was no place to hide. Take a look at the stock market. Except for energy and mining (i.e., hard stuff), there was no oasis.

Even more stunning was the bond market as the declines were historic.

The pain has been obvious in the public markets, but what isn’t so clear is who’s next? Who else is swimming naked? A few weeks ago, pension funds in the UK were the first to be exposed. Interest rates have been so low for so many years that investors were forced into higher risk/higher growth assets to make up the short-fall. Such longer-dated investments tend to be illiquid and take more time to mature. All great, but pensioners need income now. So enter liability-driven investing (“LDI”). UK pensions used LDI (i.e., derivatives) to mitigate the risk of unfunded liabilities by bridging their investments with current and expected future liabilities. Okay, but what happens if asset prices begin to fall and rates begin to move against you? Well your bridge starts to get wobbly and counterparties start asking for more collateral. Investors tend to sell the most liquid asset when faced with such margin calls, and when UK pension funds began shedding government bonds (“GILTS”) in bulk, chaos ensued.

When everyone rushed for the exit, prices plummeted, and the market froze. Interest rates spiked and the Bank of England was forced to step-in and buy bonds to “provide liquidity,” shifting from quantitative tightening to easing. Record scratch . . . wait . . . what? Yeah, UK pension funds, responsible for paying retirees effectively collapsed, but UK’s central bankers stepped-in and bailed out the industry. Yikes.

What we’re all waiting for these days is the other shoe to drop. Who’s going to be caught swimming naked and will their exposure lead to a credit crisis? We’re not worried about our banking sector. That was the last crisis. Since the GFC in ’08, we’ve heavily regulated and monitored our traditional banking industry. Today, they are well capitalized. What’s more concerning is the “shadow banking sector,” a catch-all term for non-bank financial institutions (“NBFIs”). NBFIs are an amalgamation of pension and sovereign wealth funds, ETFs, broker-dealers, trading firms, private lenders, investment banks, insurance companies, mortgage lenders, leasing companies, and yours truly . . . hedge funds.

According to the Bank of International Settlements, NBFIs account for almost 50% of global financial activities. Since NBCIs aren’t banks that take demand deposits from customers, they are relatively lightly regulated and can lend without strict leverage, capital and liquidity constraints. The sector has grown like weeds in a decade of excess and cheap liquidity as managers of all ilk used leverage to enhance returns and generate income, but what becomes of them when the illiquid assets backstopping the loans start declining in value? What happens when volatility and rising rates in the credit markets prevent NBFIs from refinancing or obtaining credit? Again, margin calls can lead to fire sales, and when they do what happens when no buyer emerges to bail you out?

We bandy about terms like systemic risk, financial contagion and collateral damage, but in the end it comes down to too much water that led to rampant speculation. Low rates and quantitative easing post-GFC gave way to unprecedented fiscal stimulus during the pandemic, and as central bankers embark on withdrawing the liquidity, things will break. If the GFC exposed traditional banks as having taken too much risk during the housing boom in the mid-2000s, then what about the other 50% of financial transactions these days? Enabled in a carefree casino, what we don’t know is the true extent of their addiction. That’s the biggest risk, and it’s so difficult to quantify.

What we do know is this . . . those that blew the bubble will own the bubble. The central bankers who want to reintroduce higher rates and moral hazard back into an undisciplined market will be forced to backtrack and bailout some of the other 50% of financial players, the shadow banks. The UK pension bailout is just the beginning because shadows can stretch far and wide. Remember, central banks are the lenders of last resort, but unlike the GFC, the one that’s unfolding today will directly impact us. Pensioners, retail investors, endowments, and non-profits, they are us, and if we bailed out monolithic “too big to fail” and politically unpopular banks, we will assuredly bail ourselves out this time around.

Just ask our British cousins.

Oil’s Central Bankers

While central bankers ratchet-up the cost of capital, the other central banker of the world, OPEC+, is increasing the cost of energy. Oil prices recently fell from a Q2 high of $120/barrel to $80/barrel, largely because of financial reasons. As we noted before . . .

“. . . the dramatic increase in volatility since the Russian/Ukraine invasion has forced banks/brokerages to increase margin requirements, thereby reducing the liquidity and number of market participants . . . the reduced liquidity leads to even more severe price swings. Higher volatility forces even higher margin requirements.”

It’s a vicious circle. Add in a palpable fear that we’re headed for a global recession and the financial markets could collapse anytime, there are few reasons to go long the oil market. While that’s all true . . . so is the fundamental tightness.

This is what we’re seeing in the oil market today. Oil on water, the amount of oil being shipped is greater (#1). Much of this is from Russian oil being shunned by the West and redirecting to the East. Longer sailing times equal more oil on water. In turn, more US barrels are being exported to Europe to cover the difference. Even as the barrels arrive, the demand pull continues to be strong from refineries, hence floating storage (#3) and onshore crude inventories (#4) continue to draw. Overall the crude is being absorbed.

If we look over on the products side, refinery margins are pretty high, which means demand for gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, etc. (for which crude is ultimately refined into) remains strong. Despite the robust inventory figures and oil prices hovering ~$90/barrel, OPEC+ recently announced a 2M bpd production cut to ostensibly combat the threat of collapsing demand. The headline reduction translates to a 1M bpd “real” cut, but it’s all a bit premature if you ask us because demand has yet to collapse. Undoubtedly some of the cuts are politically motivated (deteriorating Saudi/US relationship and Russia (the “+” in OPEC+) needs high prices to fund its war). Regardless of the reason, OPEC+ plans to decrease supplies for an entire year (until December 2023).

What’s really interesting is that before the cut, OPEC+ production growth had already started cresting. While their self-imposed quotas kept rising (i.e., allowing each country to produce more), many countries couldn’t because of physical constraints. So as we anticipated, spare capacity is dwindling. OPEC+’s latest action will set a floor for oil prices in '23 and increase spare capacity by the same amount. However, barring a global credit crisis or exogenous shock, inventories should continue to decline as demand stays steady, but supplies fall.

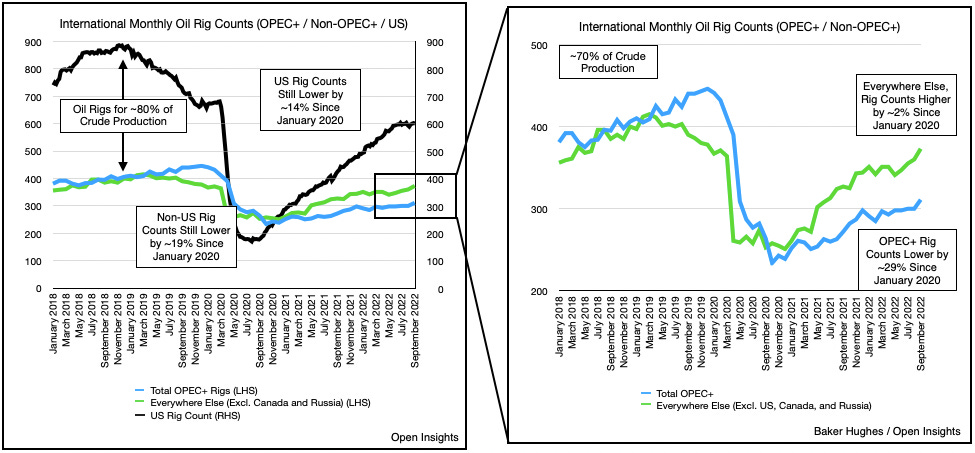

As for US producers saving us? Well we’re seeing US producer further downshift to a more sustainable lower growth, higher return model. A scarcity of parts, labor, rigs, more stringent shareholder demands, and a dearth of capital have all played a role to temper production. So for all the reasons noted, rig counts in the US (and globally for that matter) are still well below pre-COVID levels.

While demand is staying inelastic for the time being, it’s likely to increase shortly as China exits its zero-COVID-policy lock-downs. We’ve wrote about this in a recent article and encourage our partners to review it . . .

To be frank, even if the global economy were to collapse in a credit crisis, the supply/demand imbalance we’re beginning to see only worsens from here on out. The question is merely timing, if the market collapses, then it will push off the ballistic rise in energy prices for ~6 months, but it will eventually recover. If you doubt that, just step back and look again. The market is off nearly 25%, tech off by 33%, bond markets have notched historic drawdowns, and yet oil still hovers ~$90/barrel. As we exit refinery maintenance season in the coming weeks, crude demand should accelerate, and oil prices will rise again. We’ve cured none of the ills plaguing production, and will add further uncertainty as Russian oil sanctions take affect in the coming months.

This is what scarcity looks like, watch as it evolves.

Parting Thoughts

We are in an incredibly difficult market these days, one replete with high inflation, a strong Dollar, rising interest rates and falling asset prices. Central bankers around the world have been ratcheting up the cost of money, restraining it after a decade of monetary overindulgence. The dirty secret, however, is that we need inflation because we need to grow into our debt. The years of profligate spending and a COVID bailout means we can never pay back our debt, nor can we conceivably tighten our fiscal spend enough to shrink it. So before the interest payments and debt becomes too crushing, we’ll need to increase GDP (i.e., the monetary value of all finished goods and services), and slow our debt accumulation. A $100K debt is crushing if you make $20K, but $30K, $40K after inflation? Now we’re talking.

What we wrote all the way back in December 2020 is playing out, we’ll inflate our way out of this mess. Sure, we’re not growing our economy in real terms because it’s just prices that are increasing, but it at least helps optically. This is after all a big confidence game. As the economy slows, we’re desperately hoping for a Goldilocks scenario, one where inflation and interest rates balance each other out. Not too hot to break things (inflation) and not too onerous to crash things (rates). 4%? Sure that sounds about right as any, but really it’s the intensity/velocity of change that matters. The market can deal with changing circumstances if you give it enough time, but sudden changes prove challenging. Move the out of bounds lines too fast, the markets will get disorderly, investors get margin calls, debtors can’t refinance, credit markets freeze, and asset prices fall. Even if by some chance we miraculously hold together, we’re going to see more markdowns shortly. Whether accounting rules force the repricing (i.e., mark-to-market), or market transactions reset comparables, investors won’t be able to escape what’s coming. We’ll inevitably look back and wonder (as we do after every bubble bursts), how could we have been so silly, how could we have been so blind to what was so obvious?

What seemed rational during the heyday will seem foolish in hindsight . . . as my son recently reminded me . . .

Mason: If we had a bigger house, then you wouldn’t have to yell at us to pick up the toys.

Me: Well if you just picked up the toys, then I wouldn’t have to yell.

Mason: Hrmph!

Me: Jeeze la weeze, why is this guy so hard to train??

Mason: ….????….You’re trying to TRAIN ME??

Mason: (to his mom in the other room) . . . why’d you marry him??

Fortunately she didn’t hear, and with a bit of luck, I’m hoping she’ll never mark-to-market.

Please hit the “like” button and subscribe below if you enjoyed reading the article, thank you.

And another truth bomb right there. Thanks, great article.