Rising Oil Prices Will Hit Us in the CPI

September 14, 2020

We took a slight detour last week to engage in a Bear/Bull debate with HFI Research about the market today and whether we are in the midst of a tech bubble. HFI Research’s bear thesis can be found here, and ours here if you’re interested.

If you’ve been reading the newsletter, we’ve been running through some themes lately, all of them intertwined. As our political and monetary leaders clumsily navigate their way through the COVID crisis, we’ve been discussing in broad strokes the programs/policies they’ve been implementing on the fiscal and monetary front, and the potential consequences we see. We’ve written seven issues so far, and they discuss (links below):

Issue 1: Our First Newsletter

Issue 2: Get to the Choppa! Helicopter Money

Issue 3: Oil’s Impending Parabolic Recovery

Issue 4: Global Debt & the Pandemic

Issue 5: Inflation? Buckle-up . . .

Issue 7: This Isn’t a Bubble . . . That’s Coming (Part I / Part II)

The common thread to all of these topics is the impact of current fiscal and monetary policies that could lead to higher inflation. Let’s just take a look at how that could occur. In the US, we typically focus on two indices that measure inflation every month, the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) that’s released by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics every month and the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index (“PCE”) released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. As the Cleveland Fed explains

“The CPI probably gets more press, in that it is used to adjust social security payments and is also the reference rate for some financial contracts such as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) and inflation swaps. The Federal Reserve, however, states its goal for inflation in terms of the PCE.”

The CPI is based on surveys of what households buy, whereas the PCE is based on surveys of what businesses buy, so there are subtle, but important differences. They essentially come down to three things, coverage, weighting and substitution. Both the CPI and PCE track a basket of goods, ranging from food, cars, energy prices to housing costs. The baskets can be somewhat different and the relative weighting of each category can also change over time. The PCE also takes into account substitution for goods (e.g., if bread becomes more expensive, the PCE formulas will consider a new basket of goods as a substitution for people buying less bread). Lastly, the PCE downplays healthcare costs because it uses Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates vs. out of pocket “real” medical spending. The last factor is likely the most significant piece as healthcare costs are now a larger share of household spend.

Even though we keep an eye on both, for our purposes, we’ll focus on the CPI. The fact that the CPI is used as a benchmark in financial instruments means it’s a better fit for us in understanding real world inflation for investment purposes.

Inflation Du Jour

Now inflation comes in a few flavors. It’s easier to separate them into four general categories, structural inflation, cost-push inflation, demand-pull inflation and hyperinflation. Structural inflation is what we typically experience, that’s the natural rise in inflation when wages and prices steadily increase year-by-year. Cost-push inflation occurs when prices ramp up because the cost to produce the good or provide the service increases. Demand-pull inflation occurs when demand for a good/service exceeds the supply. Lastly, hyperinflation can occur when the local currency declines in real value. For instance if a country increases its money supply far in excess of what their economy needs (via fiscal and monetary policies), investors could sell the currency, thereby devaluing it. The decline in the real value of the currency forces governments to print even more money, which eventually leads to a hyperinflationary spiral.

As we’ve noted previously in our third issue, where we discuss oil, we believe that as the global economy recovers from COVID, we’re facing a supply/demand imbalance that will likely drive energy prices higher as people return to work and travel. To illustrate how inflation could occur, we’ll use energy prices as an example.

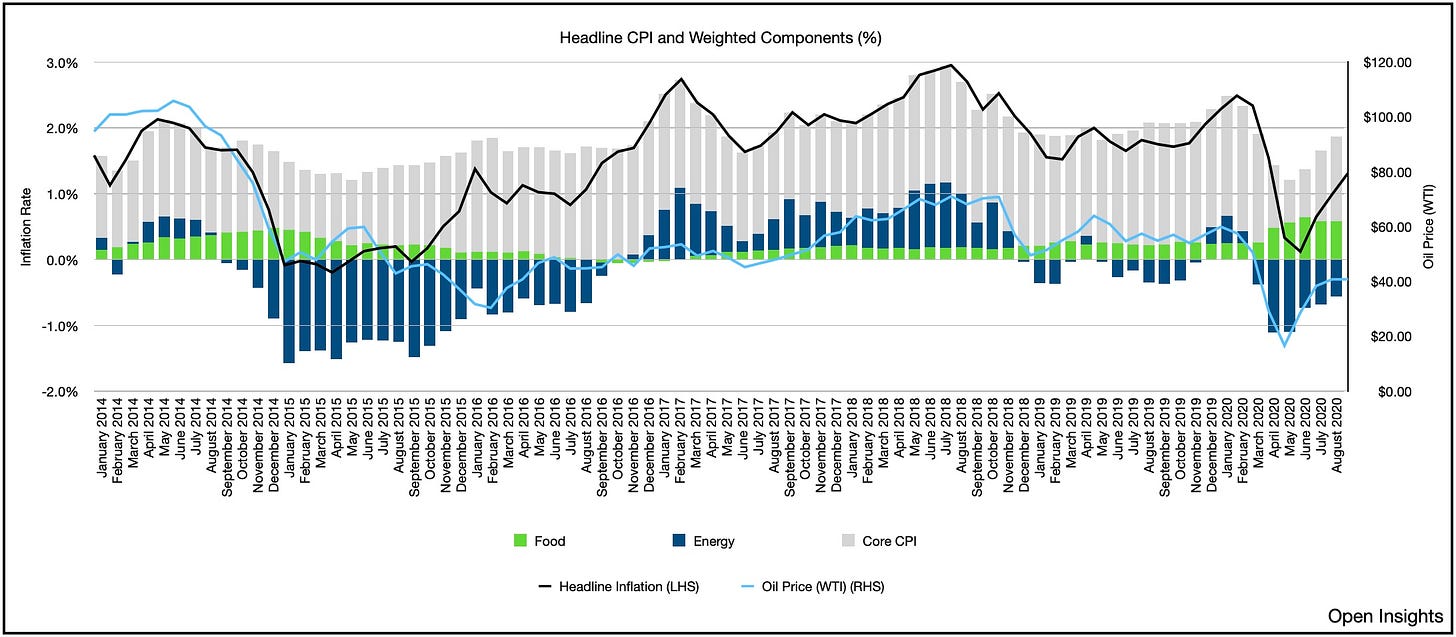

We’ve surmised that energy prices are set to rebound aggressively in the coming months/year as we recover from COVID, and if so, we anticipate demand-pull inflation to play a large role in higher inflation. Here’s the CPI chart to illustrate the impact of energy prices on inflation.

Now we’ve separated CPI into three broad categories: food, energy and“everything else” (i.e., Core CPI). The black line is the actual overall inflation, and the BLS just reported that inflation increased by 1.3% year-over-year in August. For additional reference, we’ve included the monthly average WTI oil prices (right hand side).

For the CPI’s basket of goods, energy (which includes energy commodities and services) can account from anywhere between 7-10% of the overall weighting. A material increase/decrease in energy costs though will impact not only the direct cost of energy, but also the indirect costs of other goods (e.g., rising oil prices will increase the cost of petrochemicals used in manufacturing consumer goods, the cost of plastics, and even agricultural prices). Thus, if energy prices climb and maintain a high level, what starts as a demand-pull inflation that spikes energy prices can result in a cost-push inflation for other goods/services. When energy prices rebound quickly as they did between 2016 to 2018, inflation could surprise to the upside. Notice in 2017/2018 inflation climbed above 2% as oil prices increased sharply. Conversely, note that in 2014/2015 when oil prices collapsed, a sharp decline in oil prices negated the inflation in the other baskets of goods.

Although oil prices collapsed in Q1/Q2 after COVID spread beyond the confines of Asia, they’ve since begun recovering as the pandemic’s grip has eased. Today we’re in a situation where oil supplies and inventories are declining just as energy consumption is increasing as the global economy reengages. While we still have an excess of crude and product inventories, we also have a structural supply/demand imbalance. Inventories have been drawing these past few months despite the fact that the world is only in the early stages of a recovery. Furthermore, we’re still seeing COVID flare-ups in Asia (i.e., Korea, Japan) and Europe (i.e., France, Spain, UK), which again hamper the recovery effort.

Nonetheless, six months ago, the consensus belief was that we would not have a vaccine until 2021. As vaccine research and development has progressed, people are now debating whether we’ll have an approved vaccine before or after the November election. This is a step-change. It’s an acceleration of the timeline, which means it’s an acceleration of our recovery. Said another way, a wave of demand is coming for oil as the world prepares to move again, and it’s coming faster than what many had anticipated.

Recovering GDP

Global GDP is forecasted to rise 5% in 2021, effectively recovering all that was lost to COVID in 2020. For reference, oil demand before COVID was 100M bpd (2019). Yet, even OPEC’s own Monthly Oil Market Report (September 2020) forecasts that oil demand will only reach 97M bpd in 2021. That conclusion is puzzling because how does that work? 100% GDP recovery, but only 97% recovery in oil demand? We didn’t miraculously become 3% more energy efficient in the past six months. Thus, it’s exceedingly doubtful that’s correct. Just as the Q2 period showed us how heavily we rely on oil (because even amidst a global pandemic with full-scale lockdowns, demand only declined by 10%), as we recover, our consumption patterns/habits will recover to match.

What’s actually likely happening today is conservatism. Conservatism in forecasting what could happen. With oil prices hovering below $40/barrel, inventories high, and demand recovery weak, few analysts will forecast a scenario where demand recovery will eventually outstrip spare capacity. We disagree with that for one of the same reasons we disagreed with those who previously forecasted that oil inventories would balloon by 20-30M bpd and global storage would reach tank tops. In the end, demand is relatively inelastic. People consume what they consume and if you expect a 100% global economic recovery, then guess what? Demand will rise to meet that goal. Supplies on the other hand? Well that comes down to capital, and with capital access cut-off because of weak oil prices, investors’ shift to ESG and little government support, lower future production is all but assured at this stage.

We are now weeks away from the approval of a vaccine, and a few months away from its widespread dispersal. Hence we are close to beginning the “real” global economic recovery. Before the year-end, however, we’ll have materially drawn down the accumulated COVID stocks of crude and petroleum products, after which we’ll begin to eat away at our finite global spare capacity. The likelihood of energy prices increasing is rising, and if so, demand-pull inflation plus a bit of cost-push inflation will follow as the higher energy costs ripple through the economy. Ultimately, the consequences of our collective actions during the pandemic will begin appearing as we start recovering. If we expect to fully recovery our economic footing post-COVID, we should expect to pay more if we want the same energy supplies as before.

Join the Distribution List

So that concludes this letter. Well endeavor to send these out weekly, so if you would like to be added to our distribution list, please click on the subscribe button above. This is our start and it’s our invitation for you to join us and share your thoughts. Welcome to Open Insights and let the conversation begin.