Tapering Fed / Tapping Oil

September 24, 2021

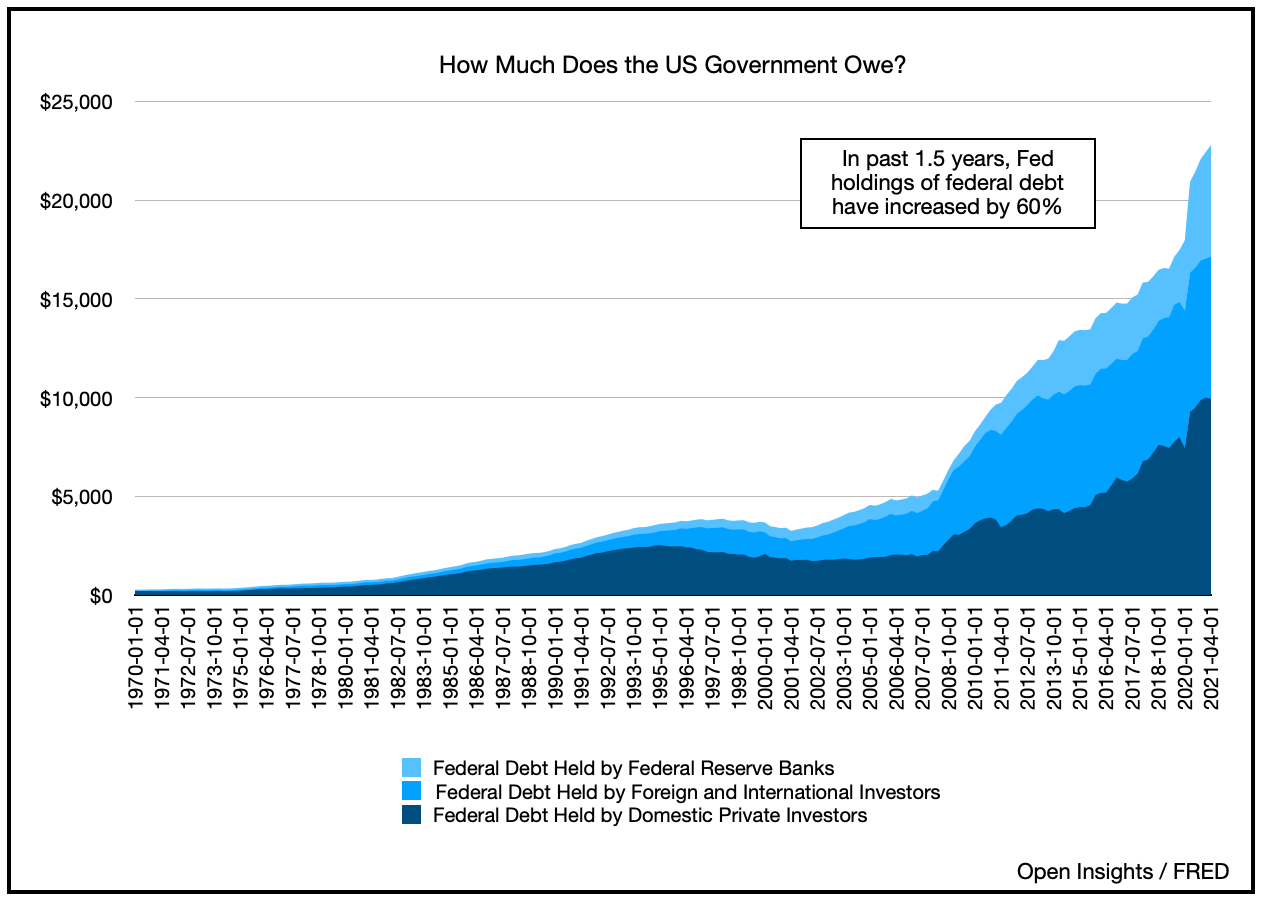

We were pulling data from the Federal Reserve (“Fed”) the other day and a few things struck us as interesting to write about. Now most of us know that the Fed has been buying treasuries hand-over-fist as they quantitatively ease (“QE") our society back from the COVID pandemic.

Yet, dig into the data and you begin to notice a few things. If Adam Smith’s invisible hand hypothetically guides the market, then the Fed’s heavy hands have manhandled the bond market. As the Fed’s embarked on QE, its treasury holdings have skyrocketed.

Compared to other investors (i.e., creditors), the pace has quickened considerably since 2020.

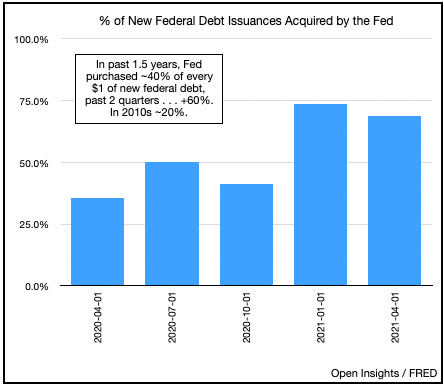

In the past year and a half, the Fed has purchased nearly 40% of the treasuries issued, and in the past two quarters it’s acquired > 65%. Said plainly, almost 2/3rd of new treasury issuances are acquired by the Fed.

This circular money printing means that the Fed is effectively crowding out all other investors in the treasury market, and its percentage of ownership of all federal debt continues to climb.

So the question we’re asking is, when the Fed begins to taper QE and the $120B of monthly bond purchases, who’s stepping into their shoes? A majority of the $120B a month is spent on treasuries, and if you’re the buyer of almost 2/3rds of the bonds issued by the government, doesn’t that present a problem? Won’t this have to go up?

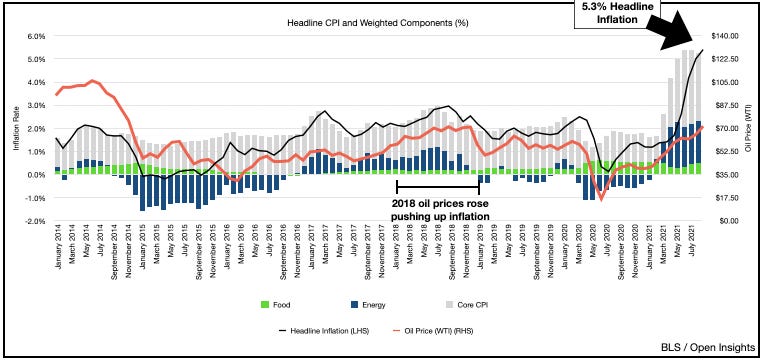

Look at how flat that 5 year rate has been, particularly recently. We have to give the Fed some credit for managing rates and inflation expectations so well, especially when CPI is flashing persistent +5% increases.

Transitory though right? As we can see in the prior chart, inflation expectations are well within 2.5% for 5 years, which we guess means that if we have 5% inflation in 2021 and 2022, then we’ll likely have essentially no inflation for the 3 years thereafter. Hmmm . . . .

Dots

Don’t let the Fed fool you, however. Despite all the “transitory” talk, the Fed is certainly aware of the issue. In its recent September meeting, the central bank dropped further hints that tapering will begin shortly (November) and finish sometime in 2022. After tapering QE, the bank then plans to raise interest rates.

On that note, we’re beginning to see a “steepening” of the Fed’s own dot plot (i.e., the internal polling of its central bankers to provide a target level for short-term interest rates (i.e., fed funds rate)).

Since the June meeting, Fed governors have grown increasingly hawkish at raising interest rates sooner and higher. All of this is translating to the 5 year treasury rate increasing even as the 30 year has held firm, which means the yield curve is flattening as rates steepen on the front end.

Effectively, the market repricing an increasingly hawkish Fed, reflecting the notion that money will get more costly as monetary authorities raise the cost of borrowing in the coming quarters. In a stock market that’s been trading at historically high levels, those rising rates aren’t going to come without some indigestion.

Note we’re not even talking about raising short-term interest rates either. We’re only talking about the prospect of tapering QE. Tapering will be our first test, but we’re doubtful that allowing rates to rise as we taper “on autopilot” will be well received by the market when it happens.

We go back to the idea that the Fed is buying up >60 cents of every dollar of treasury debt currently being issued. Remove any buyer with that kind of outsized influence from a market, be it housing, stocks, or baseball cards, we should see prices fall. In the bond market, collapsing prices will mean skyrocketing rates. In turn, higher interest rates will act like gravity to pull down asset prices across the board. So those growth stocks priced at “elevated” levels because we’re discounting future cash flows using today’s low rate? Watch what happens to their values when we adjust discount rates higher.

The Fed isn’t oblivious to any of this as we’ve seen the FOMC recently establish a domestic standing repo facility (“SRF”) and a repo facility for foreign and international monetary authorities (“FIMA”). The SRF and FIMA allow domestic and international treasury holders to place their treasuries on deposit with the Fed in exchange for US dollars. This incentivizes creditors to keep owning treasuries, instead of selling them for US dollars when they need the cash. If the Fed steps back from buying treasuries, it doesn’t want foreign or domestic creditors to add to the pressure by selling, which would reduce prices even further and lead to higher rates.

Despite all of this though, if asset prices begin to dislocate (read: fall precipitously), doesn’t the Fed pull back on its tapering? Doesn’t it also presuppose QE infinity (or at the very least a long long time)? High asset values generate a real world wealth effect, and what a recovering economy needs is a confidence boost. A dramatic downturn in the country’s net worth certainly wouldn't help matters. So therein lies our conundrum, isn’t the Fed trapped?

Truthfully we have more questions than answers at this stage, but the start of tapering begins our journey down the branching consequences of the Fed’s policies. It may take time, however, for the impacts to play out. Tapering QE over 9 months still means almost a half a trillion dollars of QE. For now, interest rates seem to be reacting to the paradigm shift, though the equity market has not. Something should give, and on balance it will likely be the stock market. So caution ahead.

Oil Update

A quick update on oil. Another week brings another data point for our energy thesis. As Hurricane Ida’s impacts wane, it’s much clearer now that while the bulk of the disruptions are fading, some lingering issues remain. Shell has announced that one of its hub platforms, WD-143, will remain offline until the year-end, which removes ~200-250K bpd of oil production from the Gulf of Mexico. We’d anticipate other producers or fields to increase production slightly to make up some of the difference, but even on the low end, we’re looking at a ~20M barrel disruption. Given that crude US inventories are at 2010-2014 levels (if we include SPR barrel), we’re already in a relatively tight market, and one that’s tightening further. Post mid-October, we’re also going to come out of “maintenance season,” which means higher overall refinery utilization/crude demand as we gather momentum into year end.

Globally we’ve seen total liquids draw by over 2M bpd. We have 2.6M bpd for the past few weeks, but some of that is because of Hurricane Ida.

Even if we stripped Ida’s effects out, we’re still looking at 1.5M bpd, which means this is a tight market despite maintenance season. It’s to be seen whether the Evergrande debacle (and all that goes into building the Chinese real estate market will impact China fuel consumption), but we doubt it’ll be a long-term impact. For now, a recovering global economy in both emerging and developed markets means a synchronized leap higher in energy consumption. In fact for many markets, consumption is already near 2019 levels. See the US . . .

With transatlantic flights to resume between the US and EU/UK in November, and transpacific flights in 2022, that’s another catalyst for fuel demand on the near term the horizon.

As for supplies, the most immediate threat to the market is Iranian barrels. Iran though, gains leverage if it drags out the JCPOA meetings. Regardless, even without a nuclear deal, Iranian crude is already flowing globally and it’s receiving a higher revenue as oil prices increase. This is likely why Iran is pushing so hard on requiring the US to lift all sanctions and hold firm to the prior JCPOA agreement. It has most of the leverage. If negotiations fail, so be it, Iran continues to develop its nuclear arsenal and barrels continue to flow onto the black market. If negotiations succeed on Iranian terms, then bonus. So at this stage Iran can keep raising with its high pocket pair, while the West is just hoping to see a flop.

What’s flopping though isn’t just global oil inventories, but what’s “in the pipeline” because remember, what’s on water today (i.e., oil on water (“OOW”)) is oil that’s making its way (or not) to hungry customers tomorrow.

These are hungry customers located onshore, who are driving, moving and manufacturing.

OOW has dropped to recent lows, but has yet to rebound. So while consumption in various countries is steadily rising, oil supplies aren’t keeping pace. Consequently, onshore oil stocks will likely further drain in the coming weeks, and as they do, prices should further rally.

Oil prices currently aren’t too hot or too cold, they are as they should be given where inventories are. Arguably they should inflect higher given where we see inventories going in the coming months, but for now, like the Fed’s tapering above, we’ll just sit back and watch things unfold.