The Lies Oil Addicts Tell

November 6, 2020

When we formulated our oil thesis, never did we imagine that a global pandemic would side-track us so that whatever returns we expected would be put-off, seemingly indefinitely.

Black swans they call it, low probability events. So much for that as it actually occurred. The thesis was fairly simple to begin with. When the price of a commodity falls below the cost to produce it, supplies will fall below demand, and prices will eventually, inevitably, rebound. Three years later in 2018, we saw that, then a US/China trade war followed by a pandemic reduced the sector to ashes. Now it’s uninvestable. Exxon’s removal from the Dow Jones Industrial Index tells you that. The Dow is supposedly a collection of 30 companies that represent the US economy, and according to its editors, oil and gas have little place in today’s modern world. Need further proof? Look across the pond and witness BP’s “strategic” shift. A company formerly called British Petroleum has decided to pivot away from its core oil and gas business to green energy. Never mind that the new business will generate half the returns of the old because this is what BP’s stakeholders supposedly want.

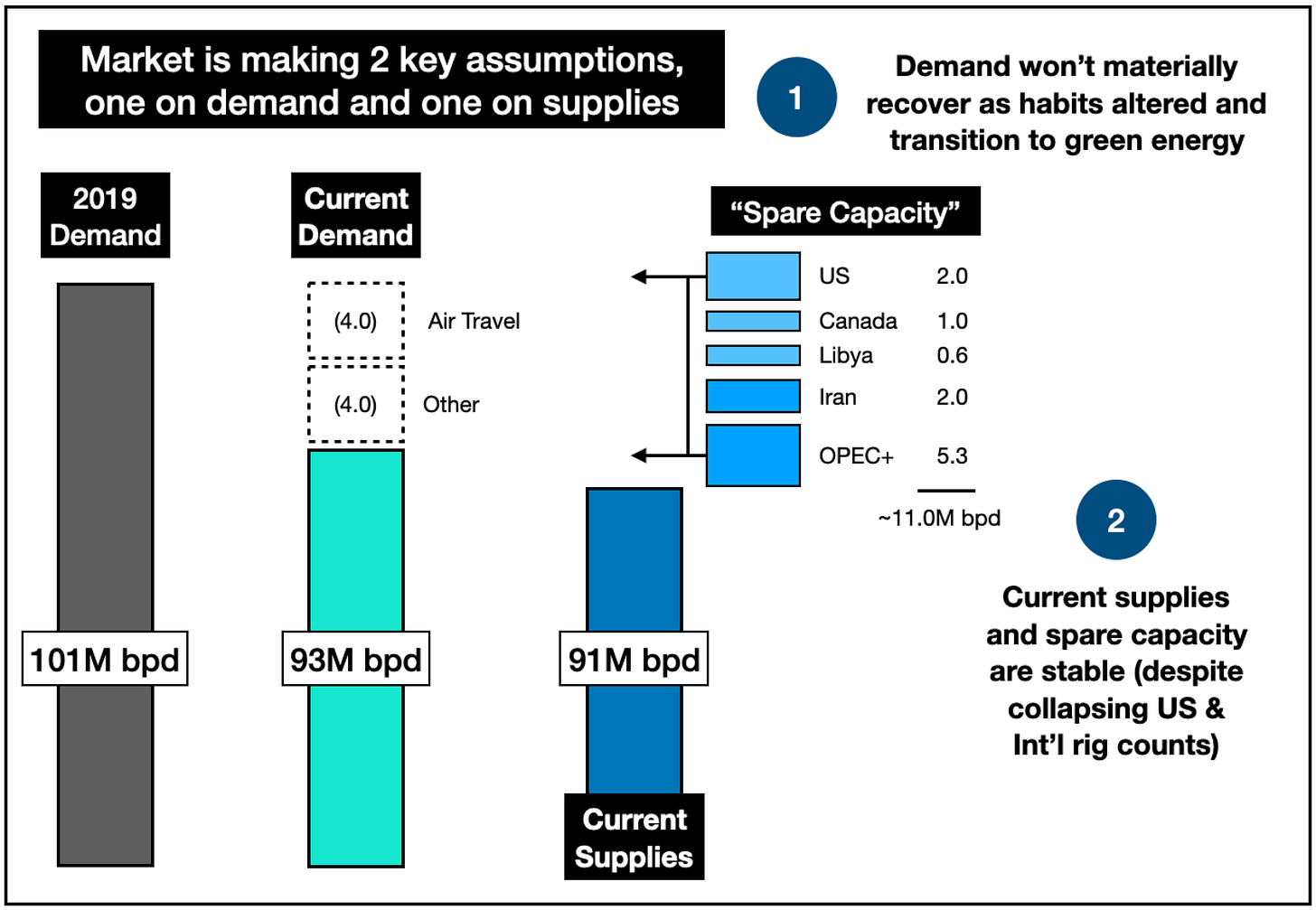

Who cares right? We don’t need it. It causes pollution, it’s horrible for the environment and we’re going green. Besides oil demand has fallen from 101M bpd to 93M bpd as of Q3 ’20, and we have over 300-400M barrels of excess liquids in visible storage and 10-12M bpd of extra capacity if we need to turn on the taps. Moreover, peak demand is around the corner because of electric vehicles (EV), reduced travel, and more people working from home will reduce our consumption. As we listen to these narratives, we marvel at how fully they’ve penetrated the market. To the point where energy as a component of the S&P 500 has fallen to a historical low of ~2%, capital has been cut off to the sector, and the potential for new capital (lending or equity raises) is close to zero with the push towards green energy.

It’s short-sightedness plain and simple. The narratives have entrenched themselves so fully that governments race to save airlines, but not the energy sector which produces the very fuel that powers the jets. The only way this is possible is because oil is simply too cheap. At $40/barrel it’s an afterthought, and the prospect of higher oil prices is inconceivable because once demand has fallen, it can never recover. Won’t it? Because we’re seeing 2M bpd draws right now, a figure that should increase as we head into year-end. After inventories rebalance, we’ll dip into our spare capacity, a supposed 10-12M bpd, but one controlled by companies and countries starved for cash and facing the prospect of owning permanently trapped resources as the world shifts to green energy. Perhaps just maybe they’ll priories debt repayments before growing production? Inconceivable.

We’ve entirely lost perspective as a society. We’ve been numbed by the dopamine and simple narratives dispensed by social media. Climate change is upon us and we need to shift, now. Like. Free money, aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus, will surely spur any requisite innovation, so we can just abandon our oil supply chain today. Yet we are globally addicted to oil and we’ve done nothing to wean ourselves from our 101M bpd addiction . . . we simply got sick. As we mend, our appetite will recover. In fact, it will likely increase as we stimulate our global economy, use more plastics for public health purposes, and shun public transportation. We persevere through this tortuous investment because othe shortages we forecasted are getting larger. We’ve done nothing to curb our addiction and the hunger pains will return when our inventories run low. What will usher in the next era of green energy isn’t our desire to combat climate change, it will be our willful neglect of energy supplies.

Oil Global Balances

In a “normal year” global demand runs around ~101M bpd, but today we’re consuming ~93M bpd. The lack of air travel accounts for half of the 8M bpd of missing demand (i.e., 3.7M bpd per Goldman Sachs). Even with the depressed demand, global inventories have been drawing by ~1.5-2.0M bpd in Q3. A combination of lower supplies, higher exports, hurricanes, and rebounding demand have helped stabilize balances.

Q4 seasonality (colder weather) should help erode the inventories as we continue to year-end. For Q4, the IEA (i.e., consensus) forecasts demand to increase quarter-over-quarter by 2.5M bpd to 96M bpd. The US, Japan, Korea, India and Europe 5 (UK, France, Germany, Spain and Italy) account for the majority of the 2.5M bpd increase, and if we conservatively assume a decrease in Europe 5 because of rising COVID cases, we’re still left with a 1.5-2M bpd increase as the other countries recover and seasonality. Consequently, global draws should rise to 3-4M bpd in the next three months. These stock draws will eventually erode the remaining excess barrels kept in floating storage (i.e., crude stored on vessels). Once normalized, onshore inventories will then drain.

Petroleum product inventories have been flat, which means the crude coming in from offshore onto land is being converted into products (i.e., gas, diesel, etc.), and refiners have been able to balance out the demand/refinery outputs. In general, crude and products inventories flip-flop during the quarter. One typically draws while the other builds.

COVID’s impact has altered that, and crude and products will likely draw together in Q4, which bodes well for total liquids to destock. By year-end we estimate that excess COVID inventories will be materially unwound. In the US, we’re seeing a draw on total liquids that parallel what we experienced in 2017-2018 when oil prices increased from ~$45 to ~$75/barrel. Global OECD balances also look similar (though we’ve provided the US/WTI chart as the data is more timely).

Air Travel

So once excess stocks are drawn, when will demand, specifically air travel begin to come back? We think within six months given our COVID outlook. By H2 2021, we’ll see a material rise in flights and passengers returning. Why? Because of survey data like this one recently released by the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

Per the IATA, 95% of those surveyed said that they would travel by air within 6-12 months after the virus is contained. What’s more surprising to us? Half of these passengers said they’d do so within 2 months after containment. As the pandemic fades, domestic travel will be the first to rebound because of lower regulatory hurdles and pent-up consumer demand. International flights, however, will depend on other countries opening their borders. This may take until H2 2021 when countries reach a certain level of vaccinations. As an interim, countries may create “air corridors,” whereby passengers who are tested before their trips can avoid quarantines (e.g., Hong Kong and Singapore). We surmise these initial regulations will serve as a template for international travel once a vaccine is released. Passengers may also need “proof of vaccination” if they want to avoid testing before traveling to another country. For our oil demand models, we conservatively assume only a partial air travel recovery for 2021. Currently, it sits well below pre-COVID levels, but US domestic air travel should continue ticking higher.

We’ve little doubt that air passengers globally will venture back in earnest once the vaccines are released. We’ve also long held that China is the world’s leading indicator on post-COVID recovery for consumer behavior. During China’s Autumn festival and week long holiday in October, travel recovered to ~70% of prior year levels. Note that this is 9 months after China’s COVID pandemic, and does not include international travel as their borders are still closed. A robust recovery indeed.

Steady Recovery

If the supply/demand deficit reaches the level we anticipate, we’ll have drawn the majority of the Q2 “COVID inventories” by year-end/ Q1 2021. Overall we’re running about 3 months ahead of the anticipated recovery path that we published in our Q1 report and finishing at 96M bpd of demand for year-end means that international air travel (globally down around 90%) is essentially the last gating item. What about supplies? Well in Q3 we’re producing ~91M bpd in a world where global demand is running about 93M bpd, which is why we’ve been seeing ~2M bpd draws. If we eventually reach 98M bpd of global demand at some point in 2021, the 6M bpd of increased demand will effectively absorb all of OPEC+’s spare capacity.

Said another way, we have crashed our oil production to the point where OPEC+ will need to produce flat out to maintain balances by 2021, and even at this level of production, we’ll be a full 3M bpd lower than our 2019 demand level of 101M bpd. If international air travel fully recovers, where does the other 3M bpd come from? Therein lies the conundrum.

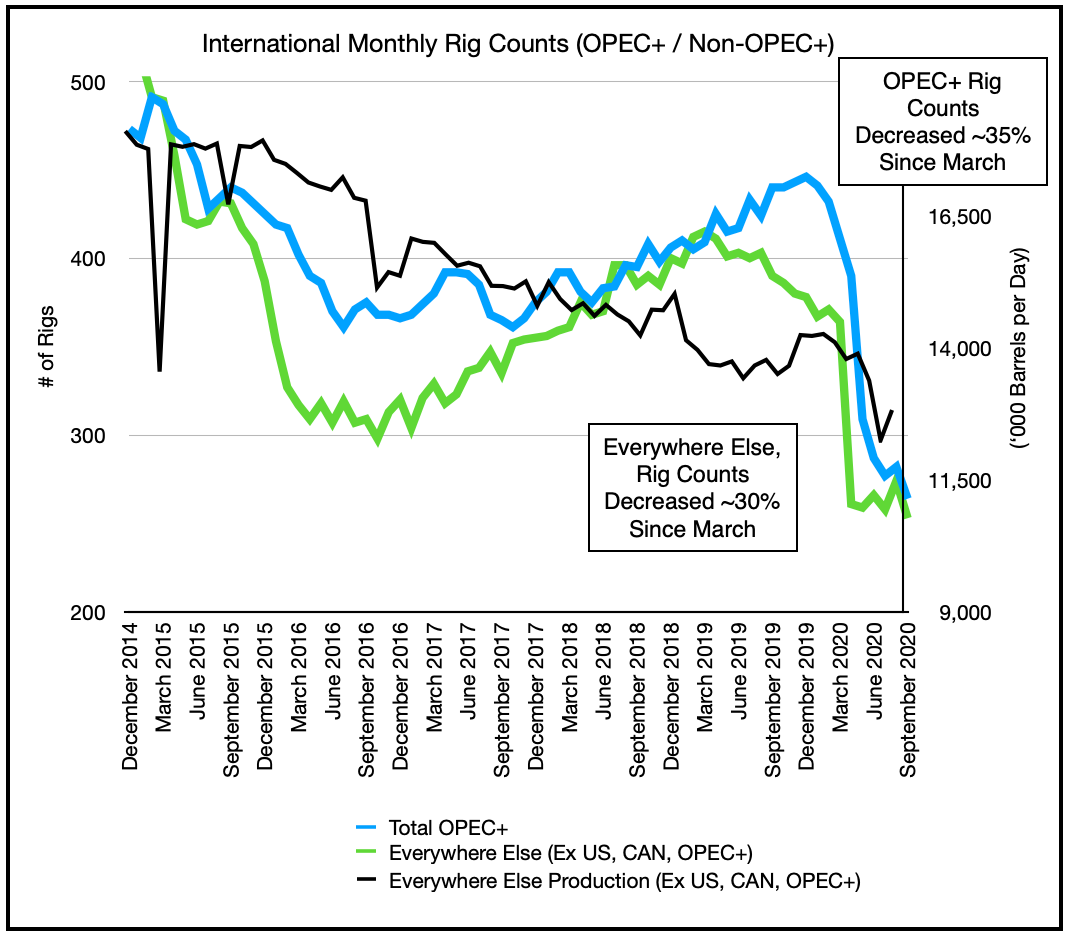

The 3M bpd gap has historically been filled by US and Canadian production, but those days are over. As banks and capital have retreated from the market, production has dipped and decline rates increased. A few months ago, US production peaked at 13M bpd. In just six months, it’s fallen to 11M bpd. Even the brief return of shut-in production hasn’t materially increased supplies, and as you can see below, US oil drilling activity is down over 70% and hasn’t increased materially these past few months.

Recent rig and frac crew additions are largely aimed at stemming the declines and stabilizing production as opposed to increasing production. Since we know that the number of completion crews directly ties to the number of wells drilled, we can say confidently that the US situation will not recover for quite awhile. We anticipate that if prices recover significantly, production will lag as producers repair balance sheets and return capital to shareholders before drilling. Given the treadmill effect of high decline rates though, the days of US reaching 13M bpd of production are likely over. Even more noteworthy is the global situation. Rig counts in countries representing almost 70% of global crude production have fallen by ~30%. Now OPEC+ is more than half of that, but the remaining portion still accounts for close to a third of global production.

We can see with the black line above (basically production everywhere else excluding OPEC+, Canada and the US) was already falling for years. The black line is an incomplete picture as JODI data fails to capture every country (and it’s self-reported), but the directional trend for years is pretty clear. Having just crashed rig counts by a third, non-US/non-OPEC+ production is also falling.

Push / Pull of Narratives and Reality

It’s difficult to convey how severe this impending energy crisis will be if we recover. We had anticipated supplies to fall short of growing demand by ~1M bpd prior to the COVID crisis and higher oil prices to ensue. Yet, what we’ve done to global production in our overreaction to this pandemic is stunning. We’ve dialed down our supplies to a level where we’ll only stay balanced if air travel doesn’t recover. To now dial production higher to meet recovering demand will be challenging given the dearth of capital, lack of investors/investments, and the continuing erosion of base production from the 5 years of underinvestment.

We believe our recovery will continue from Q4 ’20 to Q2 ’21 as vaccines become available. We further believe that people will increasingly return to work, travel, leisure, etc., and that the return will be faster than what the headlines suggest. If so, then oil demand will recover in lock-step, but oil supplies will not. We will erode almost all of the excess COVID inventories in the coming months, just as oil demand inflects higher. The outcome for these two clashing forces (higher demand / lower supplies) will be a rising oil price, which is the only thing that can incentivize producers worldwide to plug the gap.

After the pandemic recedes, it may leave us with a world where demand for fossil fuels could be higher as the use of disposable plastics and PPEs gain prevalence for public health reasons. People are also shunning public transportation and buying SUVs to drive themselves as evidenced in China. These types of unintended behavioral changes are driving real world increase in our energy consumption patterns despite the open outcry for abandoning fossil fuels. We’re saying one thing, but doing another. As Raoul LeBlanc, a Vice President at IHS Market said,

“[I]f this is the sunset time for oil and gas, someone forgot to tell consumers . . . .”

Frankly, we don’t even need demand to increase at this stage to engender a price rise, a recovery to baseline following this historic collapse will seal our fates. If it comes though, we won’t quibble because as my son points out, we shouldn’t . . .

Me: How come you chose to do the middle problem and not the harder one on the right?

Mason: . . . because . . .

Me: Because isn’t really an answer . . .

Mason: Daddy, I’m only six years old . . . don’t judge me!

We’re not judging. We’re not saying that the world shouldn’t change, we’re saying it won’t change until it needs to. Behaviors in adults are exceedingly entrenched and absent the prospect of losing life or coin, they rarely change. So until fossil fuels rise dramatically in price, we won’t, and not when compared to the heightened public health awareness post-COVID. If our forecasts on oil are correct, however, that coin will start to get costly very soon.

Join the Distribution List

So that concludes this letter. We’ll endeavor to send these out weekly, so if you would like to be added to our distribution list click on the subscribe button above. This is our start and it’s our invitation to you to join us and share your thoughts. Welcome to Open Insights and let the conversation begin.