Why We're Cynical About The Commodity Supercycle

February 16, 2021

There’s a fine line between being a skeptic and a cynic, and it’s important to understand the difference. If we look up the definition of those two words we get the following:

Skeptic - a person inclined to question or doubt accepted opinions, and

Cynic - a person who believes people are motivated purely by self-interest rather than acting for honorable and unselfish reasons.

As time moves forward, words and language tends to evolve. Skepticism today is seen as a healthy thing, question conventional wisdom and challenge the status quo. Cynicism though has taken on a negative tinge, and is oft used to describe people who are scornfully and habitually distrustful of human sincerity. It’s why there are articles proclaiming the virtues of skepticism, but the pitfalls of cynicism, or the corrosive affects a cynic can have on a team . . . lovely stuff.

So why’re we talking about semantics? Well we’ve always thought you have to have a healthy dose of both as we navigate the market. You need the first to have any hope of outperforming because you can’t outperform the indices unless you separate from the herd, and you can’t separate from the herd if you don’t question accepted opinions. Similarly you need the second because cynicism helps you understand why and how people are playing the game, it’s the motivation. Now we’re not talking about the jaded perpetually distrustful view of humanity, more of a “hint” of healthy cynicism. A droplet worth to force us to think about the players and the game.

Let’s just take a recent topic that’s prompting these thoughts.

The commodity supercycle.

This descriptor was something we saw first articulated in a Goldman Sachs analyst note published in November, which posited that we are heading towards a structural bull market for commodities because of three themes:

Revenge of the old economy - structural underinvestment in the old economy will lead to a supply shortage of critical commodities as demand inflects post-COVID;

REV’ing demand through social needs - Redistribution policies, Environmental policies and Versatile supply chains leads to cyclically stronger, more commodity-intensive economic growth; and

Revaluation and reflation - massive government largesse leads to inflation.

As commodity prices have since rallied, Goldman’s call has been prescient, and an updated note was published in January. Jeffrey Currie, Goldman’s Global Head of Commodities Research and co-author of the report continues to do the rounds on the topic, most recently in a S&P Platt’s interview that updates his thoughts. Now this isn’t an entirely unpredictable thing is it? The head of commodities research at a major investment bank calling for a commodity super cycle and pounding the table for it? Not particularly, so we noted it and went about our daily business.

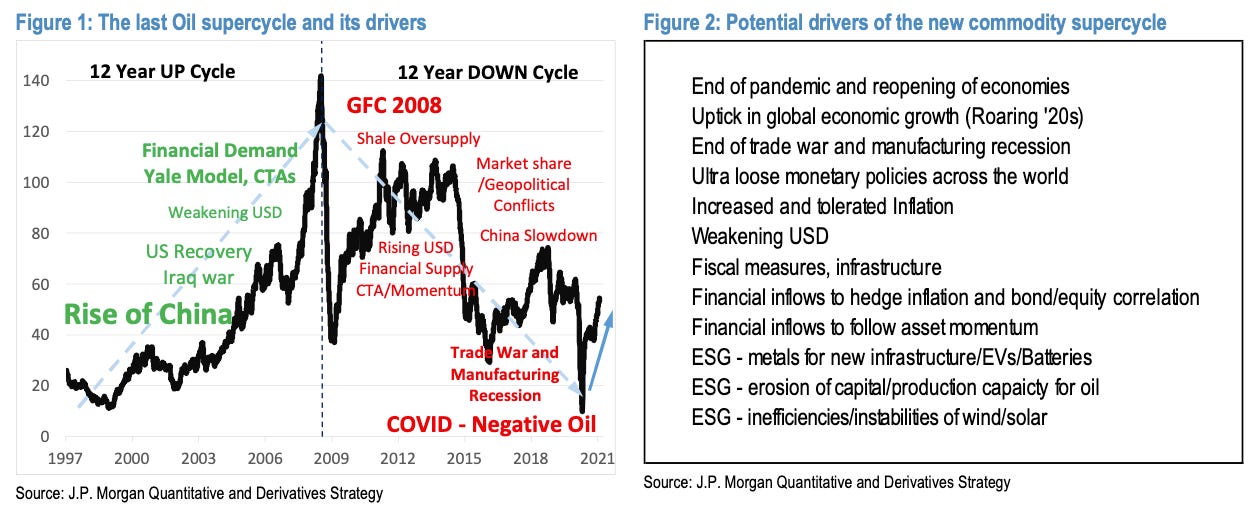

Last week, we came across another note, this time by Marko Kolanovic, JP Morgan’s Global Head of Quantitative and Derivative Strategies, who wrote that a commodity super cycle is approaching. Why? Well for these reasons.

The list essentially parallels that of Goldmans, no surprise there. It does add the element of retail investors spurring a rally, but unlike Goldman doesn’t address the supply side. Why would it though since these are quants we’re talking about?

Normally, it’s not unusual to have the same investment themes ricochet on Wall Street. If it works, hit the bid. Heck their bullish mascot is even a herd animal, and there’s great warmth in the crowd. Still, we can’t help but take notice that the views are coming from somewhat disparate crowds. It’s one thing for the commodity strategist to call for a turn on the commodity cycle, but it’s another for the quant strategist to do so. What’s even more intriguing is something that then gnawed at us.

A skeptic seeing these reports would review the analysis in detail to see if the conclusions make sense. We have and as we’ve noted previously in our own research, we can’t disagree. So though we’re part of this herd in thought, we simply think the herd is right in this instance.

A cynic though would look at the reports and deduce something different. It’s a given that people on Wall Street are self-interested . . . it’s Wall Street. What’s more interesting is if we follow the money. Always remember who the clients are for these firms. It’s not the public for whom the analysts just came out to pound the table for. It’s the funds. The hedge funds, the macro, quant, long/short, value, momo shops that pay their fees. The ones who ask the banks to make-the-market, find the counterparties, and facilitate the trades. They’re the ones analysts serve, provide your best ideas to, trade along-side-of, and bullhorn their thesis to the broader market when asked. Investment banks are part broker, casino operator, consigliere, agent, loan shark and cheerleader. Distill that and it means that if this is directionally where these analysts are going, it really means this is where their clients have already gone.

Translation: they’ve pre-positioned for the rise. Sure we can all be wrong. If Iranian barrels come back too quickly, OPEC+ cohesion disintegrates, US production discipline wanes, COVID worsens, or demand fails to return. All of these scenarios are possible, but on balance it’s more likely that demand will inflect as we globally recover from COVID. In the end, be skeptical as you walk through the pros/cons of this thesis because the questioning keeps us honest, but don’t forget to be a bit cynical in order to understand the motivations of the players. Ultimately, what we’re seeing is the casting of the fundamental die for public consumption . . . greater fools? Prepare to dive right in.